Snow is a beautiful, magical and transformative phenomenon, especially to a child. Today we’re taking a closer look at 7 snowy, wintry picture books to showcase different moods, narratives and points of view.

A reminder that the comp in Comp Titles does not stand for comprehensive – there are hundreds of books through which children and their grown-ups can enjoy snow stories and it’s not my aim to capture them all. Some go-to themes of wintertime frolic and – sledding, skiing, snowball fights, snowmen, festivities – are not included here, and does not in any way mean that those books are not treasured or very much needed. Rather, I wanted to take the opportunity to examine how else snow can lend itself to different modes of storytelling.

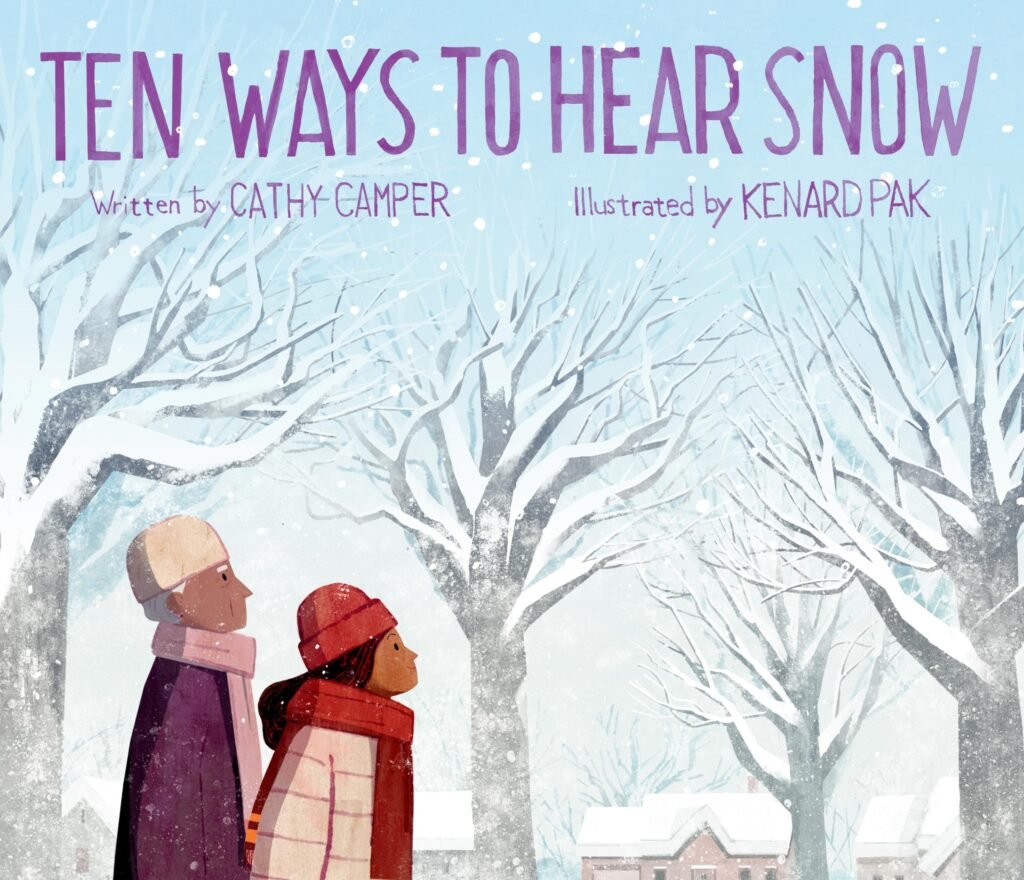

Published by Kokila, 2020

I’m starting with a story of what I hope my winters to be. Ten Ways to Hear Snow belongs to a lovely category of stories about ‘noticing.’ I love these seemingly quiet tales because observation (and with it, appreciation) is a great skill for a child to have, and something that feels like it needs to be salvaged. A child’s point of view is thought to be unique, wondrous, quirky, but what if that point of view is not a tunnel leading into a blue-lit screen, and we’re scrolling our sense of wonder away?

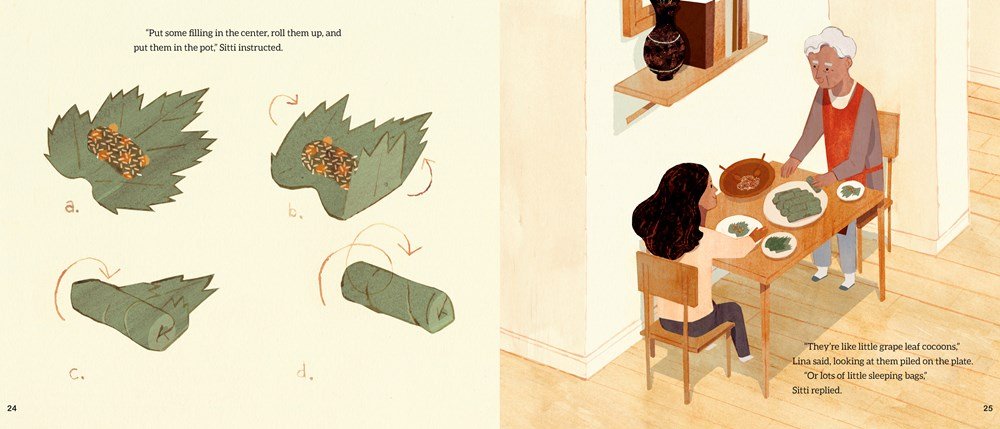

This story begins with a girl named Lina, who wakes up to find her neighbourhood covered in snow. There was a blizzard in the night, and she pulls on her winter clothes and tells her parents she wants to check on her Sitti. This term for ‘grandmother’ and the family’s tanned skin are clues of their Arabic heritage, soon confirmed by endearments like Habibti, and the fact that Lina is going over to make warak enab – stuffed grape leaves – for the day.

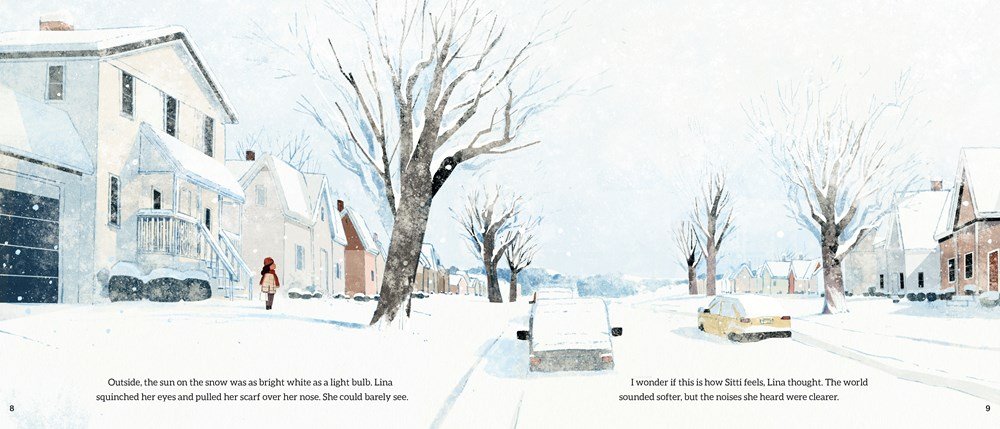

Once outside, Lina’s senses are awakened. ‘The sun on the snow was bright white as a light bulb.’ It made her squinch (I love this word!) her eyes and pull her scarf up. She wonders if this is how Sitti feels, now that she’s losing her eyesight. Lina goes to to say, ‘The world sounded softer, but the noises she heard were clearer.’

This little anchor in the story is so important for several reasons. Firstly, it brings the value of senses forward for the reader. By stating that Sitti’s eyesight is failing, Cathy has given Lina a reason to think about whether Sitti had seen the blizzard raging in the night, and how too much light can be blinding – our protagonist practices empathy.

By metaphorically ‘dimming’ her sense of sight, she now relies on her hearing, and already notices something spectacular – the clarity of noises against a muffled snowscape. It’s worth counting the different ways to hear snow, and she does!

The other thing to point out is that noticing doesn’t only happen to things that are new. It’s the way we perceive them that makes them novel. There are endearing stories that show a character discovering snow for the first time, like ‘Tiger, It’s Snowing!’ by Daishu Ma, but here, Lina clearly grew up in this environment, yet she’s able to hear and see things in a refreshingly new way.

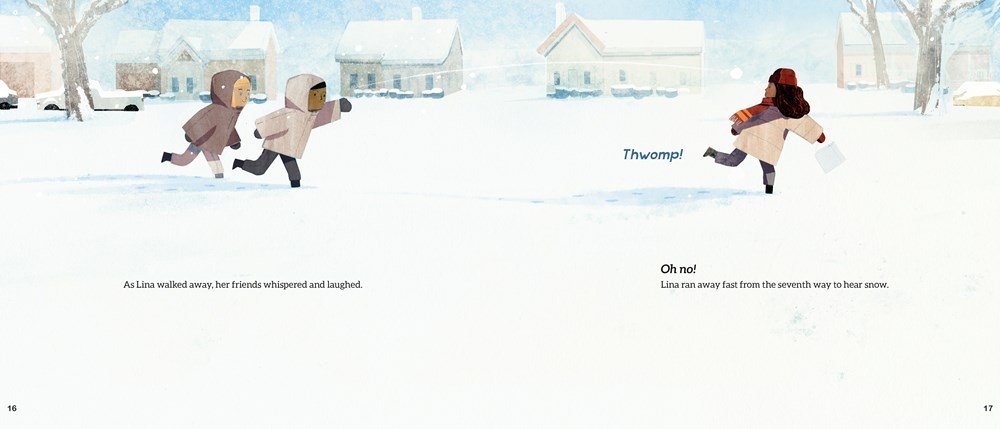

As she makes her way to her Sitti’s old folk’s home, she encounters 9 different sounds and accompanying activities. The scrip, scraaaape of a neighbor shoveling snow off their sidewalk, the snyak, snyek, snyuk of the snow under her boots and the ploompf of snow being knocked off a branch by a bluejay are the first 3 ways … the others are just as delightful.

And while the words are so fun to sound out loud, the story never veers into chaos, instead maintaining a calm pace that suits Lina’s observations, largely thanks to Kenard’s thoughtful illustrations. His snow – large white banks of it, and generous dustings on houses, cars and trees – are never overpowered by the characters of the cityscapes. He keeps a muted palette of warm fawns, greys and pale blues for walls and winter jackets, and even Lina’s pop of red scarf and beanie seem to travel unobstrusively through the landscape.

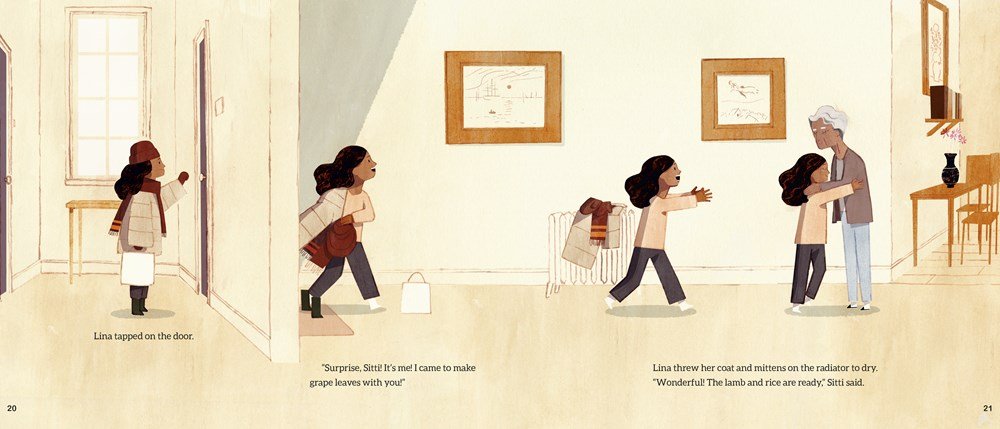

Once Lina reaches her Sitti and start to work on their warak enab, the colours indoors range from a soft sepia to a pale warm coral … except for the magenta vignettes where Lina and Sitti horse around like a ‘coupla tough guys,’ taking selfies with rolled grape leaves under their noses.

Kenard also keeps his characters’ poses tender – even during dynamic movements like skiing and running from projectile snowballs. Look out for little details that nail the gestures without exaggerating the pose – the outstretched fingers of a hand just pushed through the sleeve of a jacket, the slight lean of Lina tugging her Sitti’s hand in the kitchen. Some of his most powerful scenes, I felt, were those when Lina was still and yet very much present, looking out or up, and noticing.

Soon the food is cooked and Lina and Sitti sit down to eat together and talk about the snow. Lina’s surprised that Sitti knew about the blizzard, seeing her eyesight couldn’t have allowed her to see much outside the window, but Sitti tells her that every morning she opens the window anyway, and listens.

‘Today everything sounded hushed and soft. No noise means that it’s snowing.’

The reader is now delighted, warm and satisfied. The story is very nearly coming full circle. Lina and Sitti pull on their warm clothes and go outside to enjoy the 10th way to hear snow. I’m going to let you discover what that is for yourself, but I have a feeling you can guess what it is.

Published by Allen and Unwin, 2016

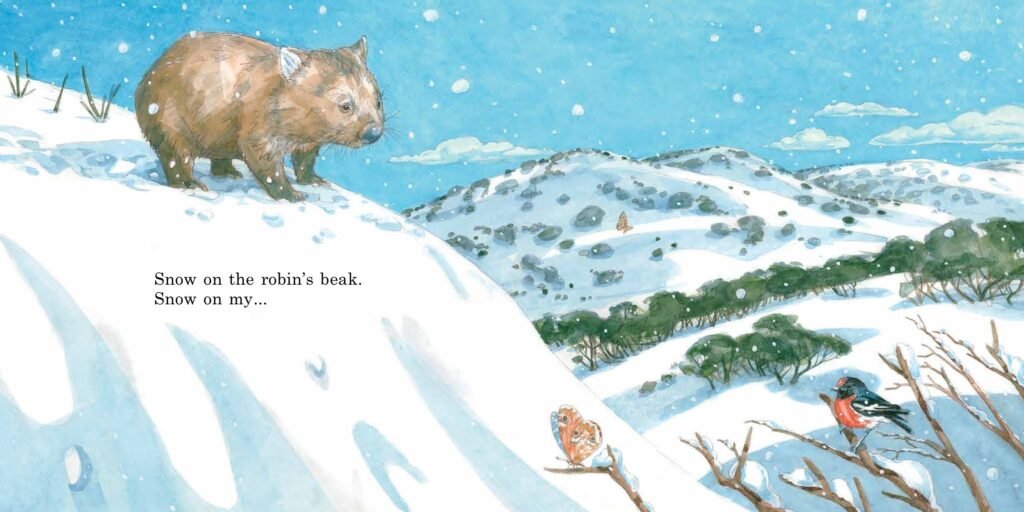

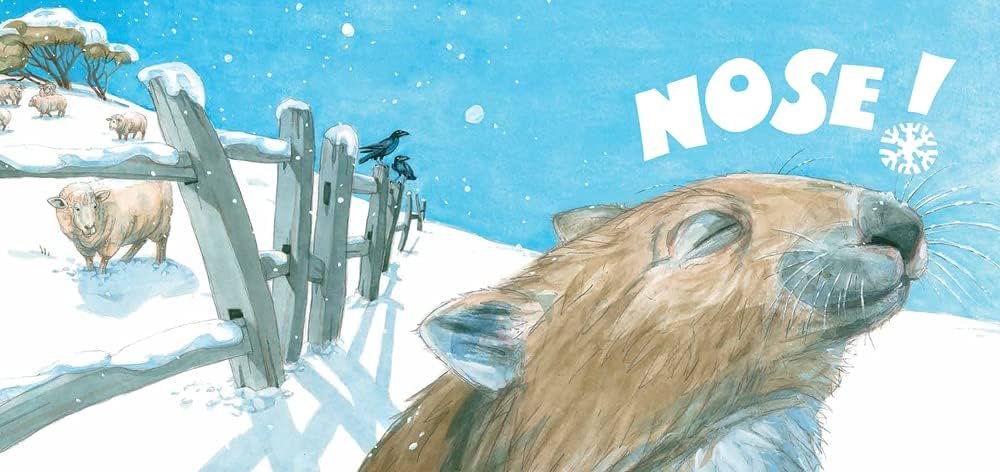

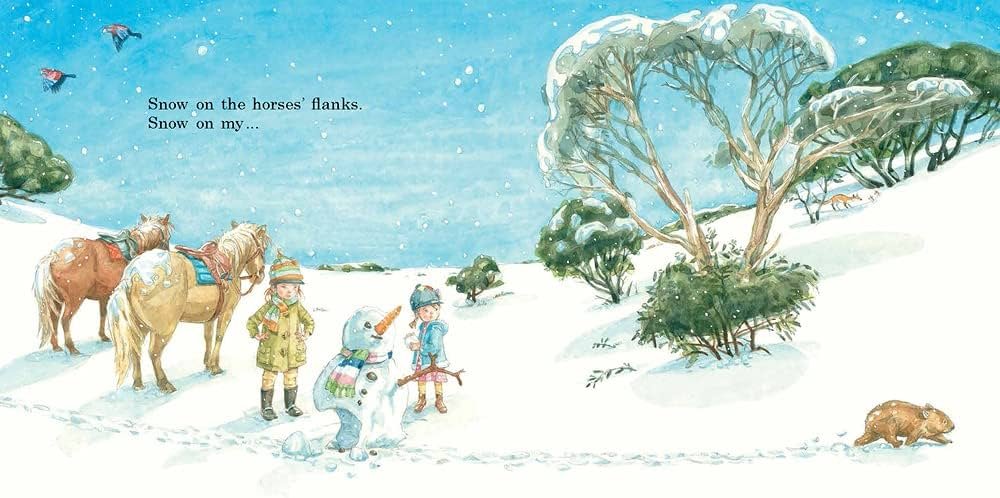

This lovely, bouncy picture book has a Down Under flavour to it, where snow arrives in the middle of the year instead of the end. Our hero is a fluffly, cuddly, and adorably clumsy native mammal, the wombat, waddling through a story that consists of 4 rhyming stanzas of only 87 words. Yet, paired with wonderful, atmospheric illustrations, it beautiful showcases the experience of snow in a rural ‘Australia.’

The lines follow a satisfying cadence that ties the description of the countryside to a body part of the wombat. The first ones go:

Snow on the stockman’s hut,

Snow on the crows.

Snow of the woollybutt.

Snow on my …

… nose!

If you’re not in the know, a stockman is a person in charge of raising animals or cattle on a farm. And a woollybutt – which I initially thought was local slang for the sheep – actually refers to a type of eucalyptus! (Thanks, Wiki!)

Mark has done wonders with Susannah’s text (which are generous in their spareness, because it allows for so much visual narrative and interpretation). The illustrations capture movement in loose scratches of graphite, and then rendered in gouache with transparent layers dabbed on to build depth and shade to the snow, and to the wombat itself, giving it shape and heft as it waddles through the snow, ripe for cuddling.

The images also give an opportunity to spot local wildlife, even when not prompted in the text. Apart from the actual wombat, kangaroo and possum, there are roadside signs warning drivers to watch out for them on the winding mountain roads. You can spot a red capped robin or something similar (there are 51 species of robins in the continent!) and maybe a bright eyed brown butterfly braving the chill.

It’s hard not to fall in love with early childhood perfection which has the added benefit of highlighting body parts like nose, tum, ears … each one coming after a page turn and featured in a double page spread with playful bold letters and snowflaked exclamation marks. It’s keeps kids guessing as to how the rhyme will end, and rewards them with a chance to shout it out.

A simple tale done brilliantly, beloved by those who live in these climes, and intriguing for the international audience. Best of all, this fantastic duo has followed up with Beach Wombat (which I actually love even more!)

Published by Quarto Publishing, 2019

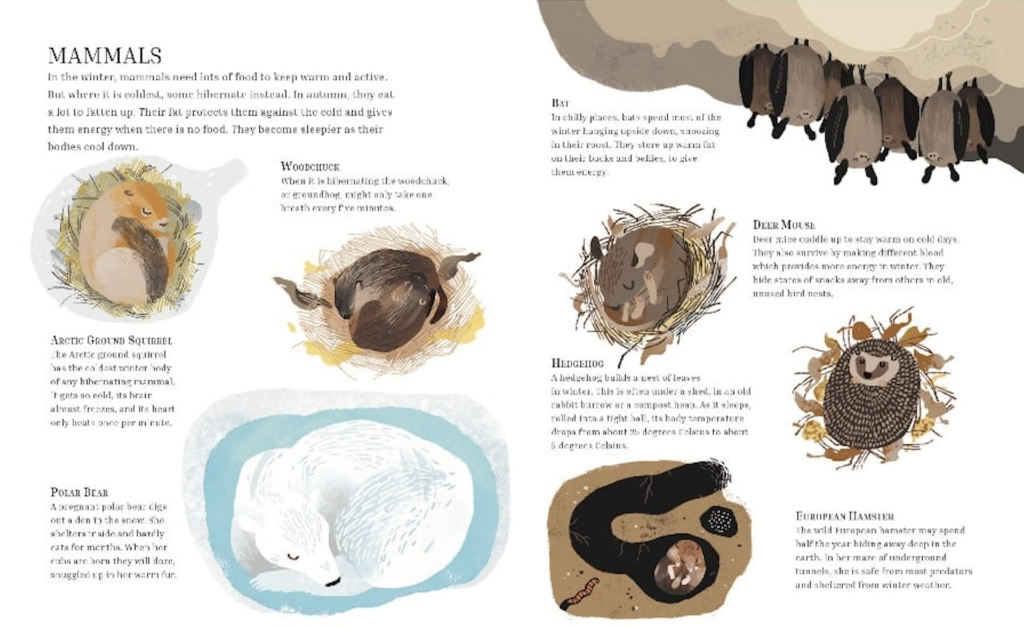

I did wonder whether wombats hibernate (they don’t really, but they conserve their energy by spending lots of time in their underground den) and though this antipodean creature is not addressed in this northern hemisphere title, lots and lots of other critters are.

Winter Sleep is part of a series which explores nature’s habits through four seasons with an effort to showcase diverse characters (including a different grown-up family member each time).

In this wintry edition, our main character is a little boy who starts by reminiscing his summers with Grandma Sylvie. The first 3 double page spreads are full of colour and warmth, and the flora and fauna are practically singing as they reach their secret glade.

When he returns in the winter, he asks Grandma Sylvie if they can visit their secret glade again. ‘Yes,’ she says, ‘if you can find it!’

The contrast in palpable. Puzzled by the complete transformation from bustling glade to stillness, quietness and colourlessness, he exclaims that nothing is alive. Grandma assures him that they are slumbering in places he cannot see, and talks through the habits of dormice, bats, insects, fish and bears.

The illustrations often show the little boy and Grandma respectfully peering and listening, as the creatures are slumbering out of sight. I really appreciate the depictions of not just the animals but their surroundings – nest, den or burrow – which is so important for young minds to visualise.

Like any good non-fiction book, there is lots of information about hibernation in the back matter and further explanations with illustrated examples specific to mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish and birds and mini-beasts, as well as simple points about how to help which further connects young ones to the environment.

I highly recommend checking out all 4 books in this series, and for an extra dose of snoozing critters, there is also HIDERS SEEKERS, FINDERS KEEPERS by Jessica Kulekjian and Salini Perera, which features more individual species with ‘info stickers’ throughout, and an index of animal tracks in the snow at the end.

As fascinating as it is to learn about how living beings adapt in the snow, a child may be curious about the way freezing weather changes objects closer to home, and for that I recommend SO COLD! By John Coy and Chris Park, which is about a little boy and his dad spending a day at home running experiments that can only be done on a freezing winter’s day.

Cute fact: all 3 creators of this book name dedicated it to their grandmothers ❄️

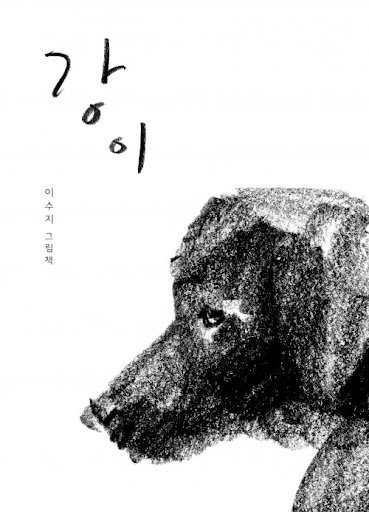

강이 (KANG-YI) by Suzy Lee

Published by BIRi, 2002 Translated to Italian as RIVER, IL CANE NERO by Giuseppe Solinas and published Edizione Corraini, 2022

Rumour has it that there’s a tried and true genre of dog stories that will bring you to tears. What is it about dog tales? Maybe it’s the simplicity of expectations – a canine friend, without the flourish of words, is able to show his or her loyalty and love in full, and innocently hopes for the same in turn without understanding the uncertainty or time, travel and change?

In River – which I think of as a picture book, though at 80 pages long it’s more of a diary – Suzy Lee pares back this simple premise of love and friendship even more by using as few words as possible (188 words in the Italian version I bought in Bologna in the year that Suzy was honoured with the H.C. Andersen Award) and by illustrating largely with what seems to be charcoal (or maybe black crayon?) on white paper.

The white paper is of course, snow. On the first spread, there is a simple drawing of a caged dog on the right, and two words on the left:

Hungry.

Thirsty.

How starkly, honestly and completely this story begins. Our hearts are pierced and we turn the page cautiously to see what happens next. In the same spare black marks, a story is etched out on a canvas of white.

A neighbor feeds the black dog, confronts the owner, takes control and brings him to the vet. The dog is unwell and needs care and a lot of space. ‘You have a garden at home, right?’ the vet asks. The rescuer, April, laments ‘This place is too small for three!’ and makes another phone call.

Those who had gardens arrived.

At the new destination, the black dog is greeted by 2 children who introduce themselves as Lightning and Thunder. Their grandfather’s cat is Cloud, so of course, the dog is now ‘River.’

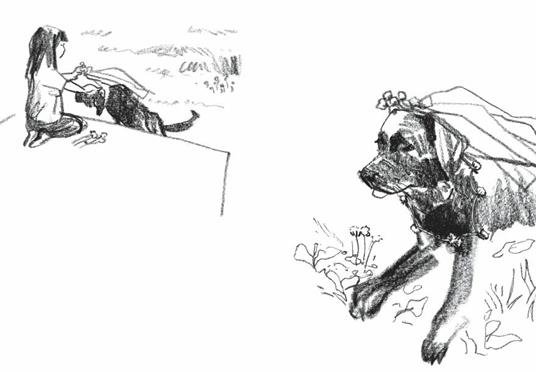

The following pages contain very little words, and in fact, very few lines. But within that sparseness, every stroke counted. Suzy scratched leafless trees in the foreground and background of the winterscape where River was ‘not hungry, not thirsty and no longer bored.’

Extra strokes and smudges for a wagging tail. Bold lines for squinching eyes in the bath, the slant of a dog almost detached from his shadow as he runs, the open armed gait of a child, the hilarious permission given to a child to dress him in a bridal veil, the snowman, the zoomies, the crash and flurry of snow. And suddenly, River sitting alone, watching the children leave.

By now Suzy has full control of our emotions. Our heart sit in her charcoal-stained hands (or is it crayon?) , and she runs her instrument across the entire double page spread, so that River is staring into the night, alone.

The next day he’s back at the vet, who squats down with Grandfather to find out why ‘River is not well. Not good at all.’ Back in the yard, he lies low and waits, only raising his head when new snow falls, blue this time.

Suzy offers no more words now. Just black marks padding footprints through blue snow.

It’s really the second last scene that gets me. It’s a movement that someone like me, who has never had a dog, could recognize – the helter-skelter run of pure-unbridled excitement as River throws his body in motion towards the ones that he loves.

It is incredible – INCREDIBLE – how carefully chosen gestures can convey so much, and Suzy does this brilliantly. I later find out that this story is based on her own experiences, and the illustrations are based on sketches of the real River.

The story ends with River’s black snout, paws and softly closed eyelids sandwiched between the blue silhouettes of two young children, the snow falling hard around them.

And me in a puddle of tears.

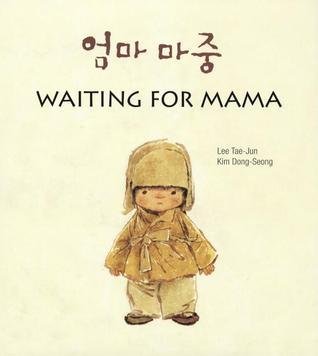

WAITING FOR MAMA

Bilingual Korean and English edition published by North-South Books, 2006

Something about the last pages of River made me think of another book my Korean creators, and what I love about this story – aside from its tenderness – is that the author and illustrator belonged to two completely different eras, and were never alive at the same time.

Lee Tae-Jun was born in 1904 and wrote under the pen-name Sangheo. He wrote novelettes and many short stories, including this one which appeared in a newspaper in 1938. He died in North Korea in 1956.

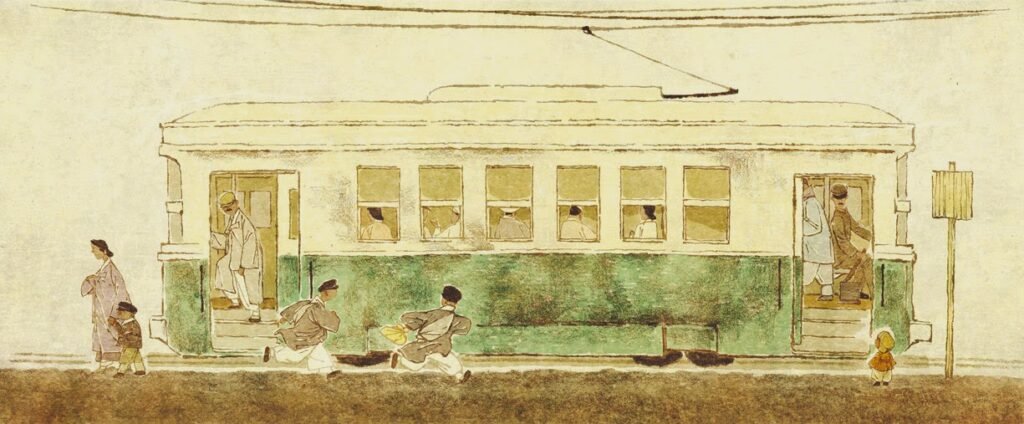

The illustrator, Kim Dong-Seong was born in 1970, and drew the scenes as you may see them in Seoul in the 1930s. There is no doubt that Dong-Seong’s watercolours on sepia-tinted paper convey an old world feel.

He draws the little boy wrapped up in winter garments and hat, melting our hearts with his red nose and little legs as he climbs onto the streetcar platform. Every time a streetcar pulls up he asks the driver,

“Isn’t my Mama coming?”

The first guy is pretty curt. ‘Do I know your mama?’ he says before driving off. The little boy is undeterred. He waits and asks each time a streetcar pulls up. The next driver is a lot nicer. He steps out to check on the boy and advises him to stand back while he waits; he’s sure his Mama will come along soon.

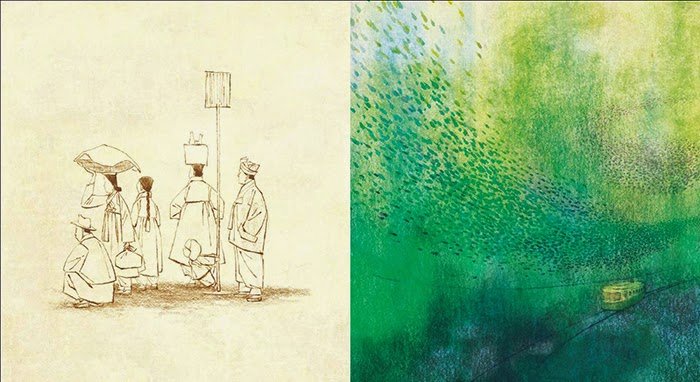

The monotone drawings where the child stands patiently waiting while the bustle of city life goes past is a wonderful peek into old Korea. Men cycle past store fronts, women dressed in hanbok, balancing bundles in their arms, strapped to their back, or on their heads. These scenes are alternated with full colour images of the streetcar approaching, sometimes zooming Ghibli style through slanted colourful snow, sometimes ethereal as it drives under an enormous tree. In an interview, the illustrator Dung seong says that he used monotone for the parts of the story rooted in real life, and full colour for the imaginary part.

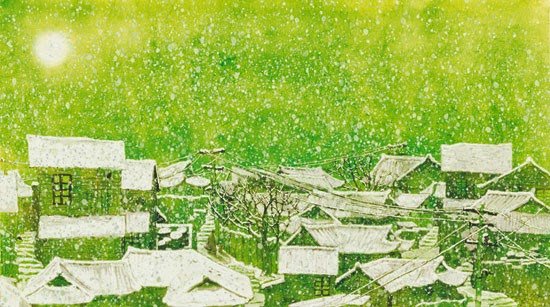

Where does that leave us by the end? The boy is now alone looking up at the heavy snowfall. The winter landscape is not white, but green.

In the final spread, you might, as I did, clutch my chest. Where I had hoped for a beautiful reunion of mother and son, I’m left with a stunning image of a Korean neighbourhood, silenced by snow and dying light.

The fact that Tae-Jun Lee was an orphan played on my mind. Was there more to this story than I signed up for?

But look closely, and you might find something unexpected.

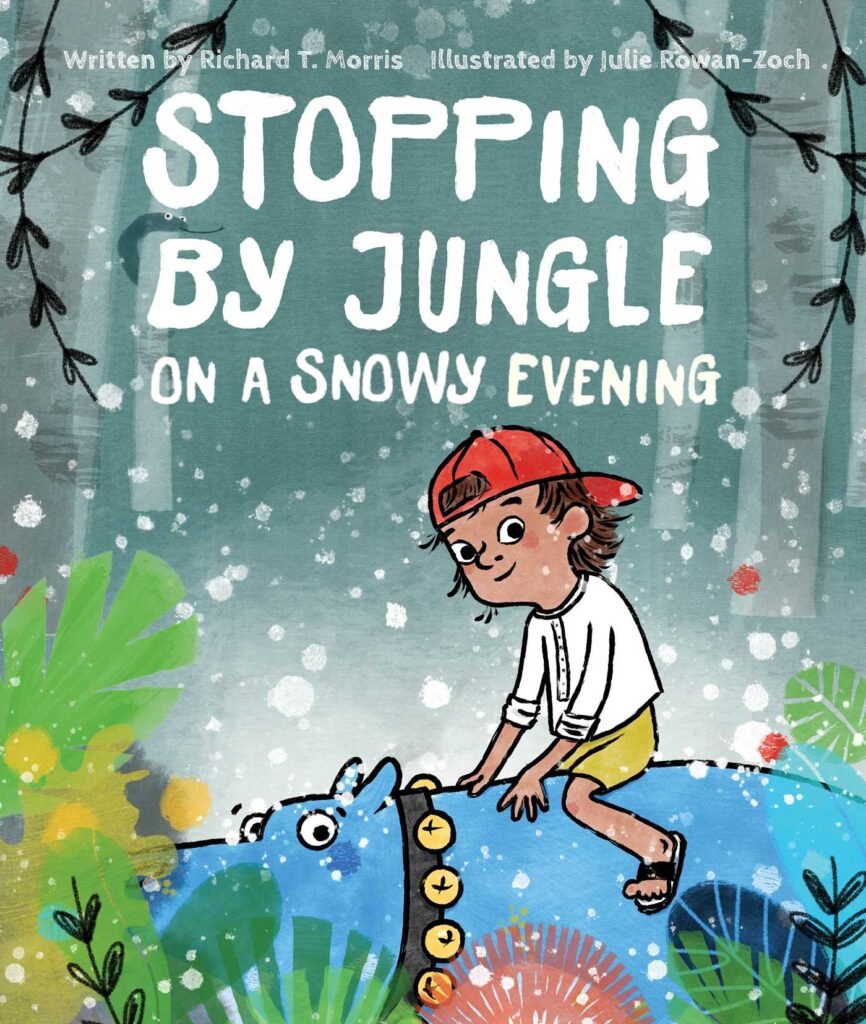

Published by Caitlyn Dlouhy Books, an imprint of Atheneum Books for Young Readers, 2024

I end this list with one of the newest releases this year, and a super fun one. Sometimes random, bizarre and totally crazy really works, and this is one of those times.

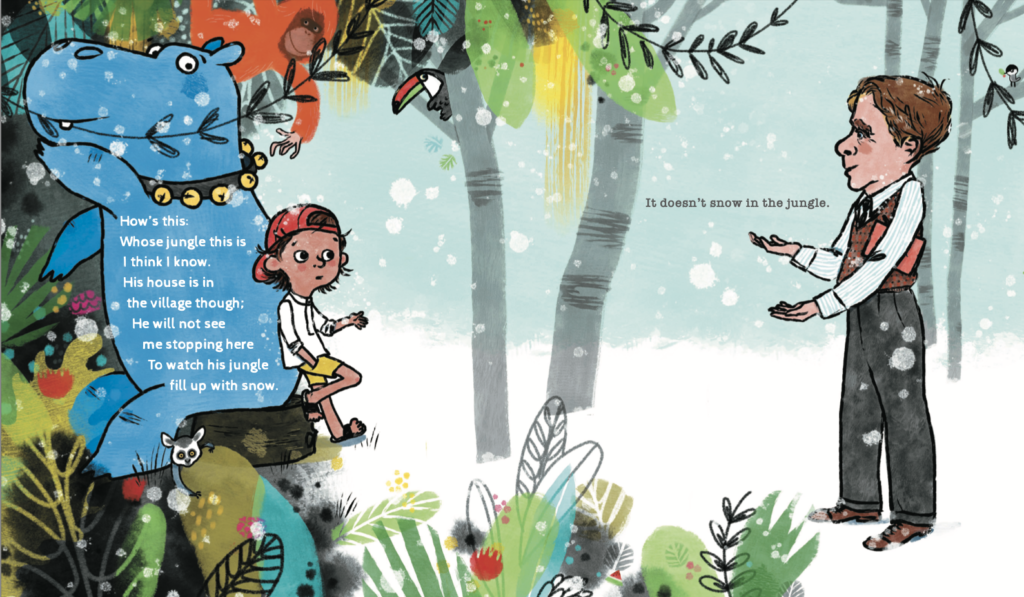

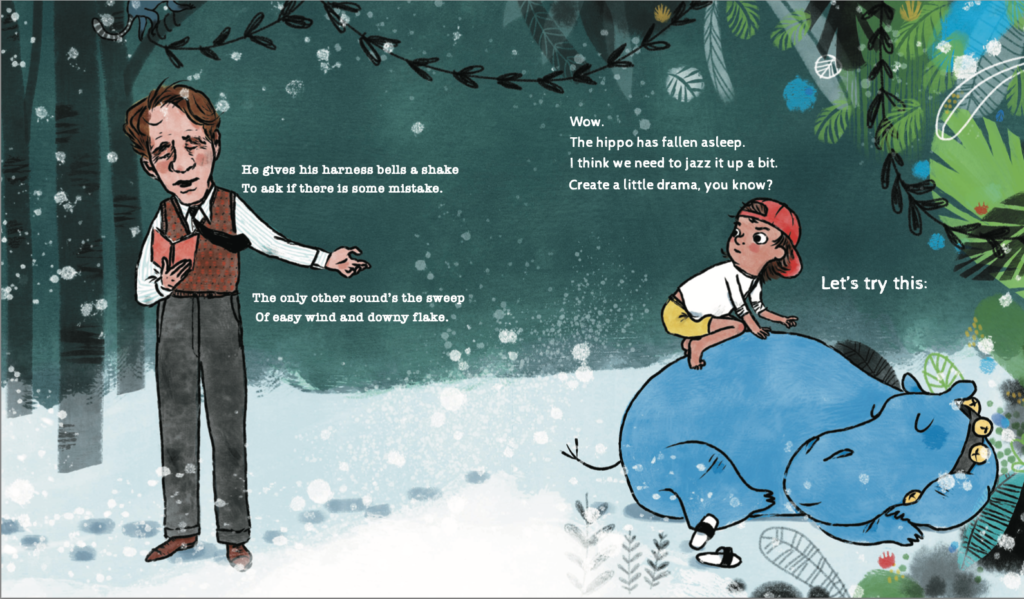

This chaotic story is a play on Robert Frost’s poem, Stopping By Woods on a Snowy Evening. The original poem is included in the back matter and we meet the Robert Frost himself, though not before travelling a little ways with our baseball-cap sporting main character who is riding a a big blue hippo wearing bells. ‘Jingle! Jingle!’

Nothing unusual here! Just a boy on his ride reciting that famous Robert Frost poem, until of course he tries to substitute ‘horse’ with ‘hippopotamus’ in the second stanza, at which point THE Robert Frost climbs out a window and interjects.

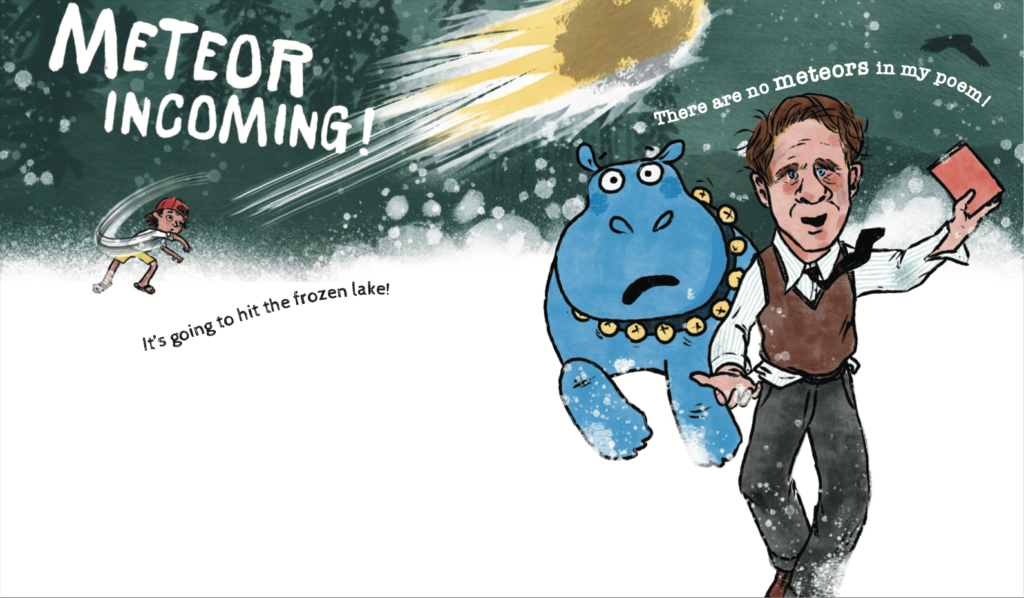

The kid is excited about meeting a ‘real life writer’ and tries to convince him to change things up. When Frost points out that hippos live in the jungle, not the woods, their surroundings turn verdant and vine-y and the snow turns to rain. Rain of course, doesn’t rhyme with snow, so they may as well have… dough!

The rest of the book is a ridiculous attempt to rhyme without reason, which echoes the ‘everything goes’ style of story-telling and play that kids are so brilliant at, and I can see them having a ball as they read this book (which, by the way, enlightens them to not one but TWO classical poems, as it transitions at the end into Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken).

The illustrations are totally wacky, with bold outlines, deep colour and a contrast between the cartoon style of boy and hippo and the caricature-like appearance of Mr Frost. My favourite scenes are of Robert Frost reciting his poem solemnly in the snow, arm stretched out to the side, fingers gripping an imaginary angst … and the hippo’s face as it’s running from a meteor.

A great comp title to this comp title is The Book That Almost Rhymed by Omar Abed and Hatem Aly, where the poet is not Robert Frost, but a little boy and his rhyming nemesis is an annoying (but secretly brilliant) little sister.

We made it! Do you feel cold? Do you feel warm? Hopefully a bit of both. It’s been fascinating to see how many stories and worlds have unraveled in this shared setting.

Here are a few questions as you mull over the comp titles and seek out more –

What emotions and moods lend themselves most to snow? If you find answers in both extremes, what is it that brings one out rather than the other?

How is snow observed in different cultures and countries? What is the significance of diverse characters like Lina (and Ezra Jack Keats’ Peter) in the current mainstream market?

How do the illustrations differ, and what effect do they have? Do Kenard’s barely-there outlines, Mark’s pencil scratches, Suzy’s bold marks and Julie’s thick black lines lead to different experiences? What other elements – colour, composition, perspective – can you compare and contrast?

And lastly, would you like more of this? Let me know all your answers in the comments!